Wally Wood is a popular comic book artist.

References

* * *

Wally Wood

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Wally Wood | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait by Wally Wood | |

| Born | Wallace Allan Wood June 17, 1927 Menahga, Minnesota |

| Died | November 2, 1981 (aged 54) Los Angeles, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) |

|

| Pseudonym(s) | Woody |

| Awards | full list |

Wallace Allan Wood (June 17, 1927 – November 2, 1981) was an American comic book writer, artist and independent publisher, best known for his work on EC Comics's Mad and Marvel's Daredevil. He was one of Mad's founding cartoonists in 1952. Although much of his early professional artwork is signed Wallace Wood, he became known as Wally Wood, a name he claimed to dislike.[1] Within the comics community, he was also known as Woody, a name he sometimes used as a signature.

In addition to Wood's hundreds of comic book pages, he illustrated for books and magazines while also working in a variety of other areas — advertising; packaging and product illustrations; gag cartoons; record album covers; posters; syndicated comic strips; and trading cards, including work on Topps' landmark Mars Attacks set.

EC publisher William Gaines once stated, "Wally may have been our most troubled artist... I'm not suggesting any connection, but he may have been our most brilliant".[2]

He was the inaugural inductee into the comic book industry's Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1989, and was posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1992.

Biography

Early life and career

Wally Wood was born in Menahga, Minnesota, and he began reading and drawing comics at an early age. He was strongly influenced by the art styles of Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon, Milton Caniff's Terry and the Pirates, Hal Foster's Prince Valiant, Will Eisner's The Spirit and especially Roy Crane's Wash Tubbs. Recalling his childhood, Wood said that his dream at age six, about finding a magic pencil that could draw anything, foretold his future as an artist.[1]

Wood graduated from high school in 1944, signed on with the United States Merchant Marine at the beginning of World War II and enlisted in the U.S. Army's 11th Airborne Paratroopers in 1946. He went from training at Fort Benning, Georgia, to occupied Japan, where he was assigned to the island of Hokkaidō.

In 1947, at age 20, Wood enrolled in the Minneapolis School of Art but only lasted one term.[3] Arriving in New York City with his brother Glenn and mother, after his military discharge in July 1948, Wood found employment at Bickford's restaurant as a busboy. During his time off he carried his thick portfolio of drawings all over midtown Manhattan, visiting every publisher he could find. He briefly attended the Hogarth School of Art but dropped out after one semester.

By October, after being rejected by every company he visited, Wood met fellow artist John Severin in the waiting room of a small publisher. After the two shared their experiences attempting to find work, Severin invited Wood to visit his studio, the Charles William Harvey Studio, where Wood met Charlie Stern, Harvey Kurtzman (who was working for Timely/Marvel) and Will Elder. At this studio Wood learned that Will Eisner was looking for a Spirit background artist. He immediately visited Eisner and was hired on the spot.

Over the next year, Wood also became an assistant to George Wunder, who had taken over the Milton Caniff strip Terry and the Pirates. Wood cited his "first job on my own" as Chief Ob-stacle, a continuing series of strips for a 1949 political newsletter. He entered the comic book field by lettering, as he recalled in 1981: "The first professional job was lettering for Fox romance comics in 1948. This lasted about a year. I also started doing backgrounds, then inking. Most of it was the romance stuff. For complete pages, it was $5 a page... Twice a week, I would ink ten pages in one day".[4]

Artists' representative Renaldo Epworth helped Wood land his early comic-book assignments, making it unclear if that connection led to Wood's lettering or to his comics-art debut, the ten-page story "The Tip Off Woman" [sic] in the Fox Comics Western Women Outlaws #4 (cover-dated January 1949, on sale late 1948). Wood's next known comic-book art did not appear until Fox's My Confession #7 (August 1949), at which time he began working almost continuously on the company's similar My Experience, My Secret Life, My Love Story and My True Love: Thrilling Confession Stories. His first signed work is believed to be in My Confession #8 (October 1949), with the name "Woody" half-hidden on a theater marquee. He penciled and inked two stories in that issue: "I Was Unwanted" (nine pages) and "My Tarnished Reputation" (ten pages).

Wood began at EC co-penciling and co-inking with Harry Harrison the story "Too Busy For Love" (Modern Love #5), and fully penciling the lead story, "I Was Just a Playtime Cowgirl", in Saddle Romances #11 (April 1950), inked by Harrison.

1950s

Working from a Manhattan studio at West 64th Street and Columbus Avenue, Wood began to attract attention in 1950 with his highly detailed and imaginative science-fiction artwork for EC and Avon Comics, some in collaboration with Joe Orlando. During this period, he drew in a wide variety of subjects and genres, including adventure, romance (which he really didn't care for) war and horror; message stories (for EC's Shock SuspenStories); and eventually satirical humor for writer/editor Harvey Kurtzman in Mad including a satire of the lawsuit Superman's publisher DC filed against Captain Marvel's publisher Fawcett called "Superduperman!" battling Captain Marbles.

Wood was instrumental in convincing EC publisher William Gaines to start a line of science fiction comics, Weird Science and Weird Fantasy (later combined under the single title Weird Science Fantasy). Wood penciled and inked several dozen EC science fiction stories, many considered classics. Wood also had frequent entries in Two-Fisted Tales and Tales from the Crypt, as well as the later EC titles Valor, Piracy and Aces High.

Working over scripts and pencil breakdowns by Jules Feiffer, the 25-year-old Wood drew two months of Will Eisner's classic, Sunday-supplement newspaper comic book The Spirit, on the 1952 story arc "The Spirit in Outer Space". Eisner, Wood recalled, paid him "about $30 a week for lettering and backgrounds on The Spirit. Sometimes he paid $40 when I did the drawings, too".[5]

Feiffer, in 2010, recalled Wood's studio, "which was at that time in the very slummy Upper West Side [of Manhattan] in the [West] 60s, years before it was [the] Lincoln Center [area]. It was a cartoonist and science-fiction writers' ghetto — just a huge room where the walls were knocked down, dark, smelly, roach-infested, and all these cartoonists and writers bent over their tables. One was [science-fiction writer] Harry Harrison."[6]

Between 1957 and 1967, Wood produced both covers and interiors for more than 60 issues of the science-fiction digest Galaxy Science Fiction, illustrating such authors as Isaac Asimov, Philip K. Dick, Jack Finney, C.M. Kornbluth, Frederik Pohl, Robert Silverberg, Robert Sheckley, Clifford D. Simak and Jack Vance. He painted six covers for Galaxy Science Fiction Novels between 1952 and 1958. His gag cartoons appeared in the men's magazines Dude, Gent and Nugget. He inked the first eight months of the 1958-1961 syndicated comic strip Sky Masters of the Space Force, penciled by Jack Kirby. Wood expanded into book illustrations, including for the picture-cover editions (though not the dust-jacket editions) of titles in the 1959 Aladdin Books reissues of Bobbs Merrill's 1947 "Childhood of Famous Americans" series.[7]

Silver Age/Bronze Age

Wood additionally did art and stories for comic-book companies large and small — from Marvel (and its 1950s iteration Atlas Comics), DC (including House of Mystery and Kirby's Challengers of the Unknown), and Warren (Creepy and Eerie), to such smaller firms as Avon (Strange Worlds), Charlton (War and Attack, Jungle Jim), Fox (Martin Kane, Private Eye), Gold Key (M.A.R.S. Patrol Total War, Fantastic Voyage), Harvey (Unearthly Spectaculars), King Comics (Jungle Jim), Atlas/Seaboard (The Destructor), Youthful Comics (Capt. Science) and the toy company Wham-O (Wham-O Giant Comics). In 1965, Wood, Len Brown, and possibly Larry Ivie[8] created T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents for Tower Comics. He wrote and drew the 1967 syndicated Christmas comic strip, Bucky's Christmas Caper.[9] In 1970, he was a ghost artist for an episode of Prince Valiant.[citation needed]

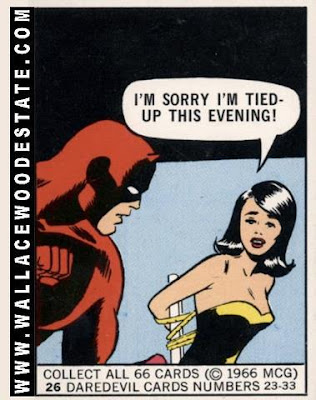

Daredevil #7 (April 1964): Wood's best-known work for Marvel, debuting Daredevil's modern red costume

For Marvel during the Silver Age of comic books, Wood's work as penciler-inker of Daredevil #5-8 and inker (over Bob Powell) of issues #9-11 established the title character's distinctive red costume (in issue #7; see cover at left). When Daredevil guest-starred in Fantastic Four #39-40, Wood inked that character, over Jack Kirby pencils, on the covers and throughout the interior.[10] (In one of his final assignments, Wood returned to a character he helped define, inking Frank Miller's cover of Daredevil #164 [May 1980].)

Wood also penciled and inked the first four 10-page installments of the company's "Dr. Doom" feature in Astonishing Tales #1-4 (August 1970 - February 1971), and both wrote and drew anthological horror/suspense tales in Tower of Shadows #5-8 (May–November 1970), as well as sporadic other work.[11]

In circles concerned with copyright and intellectual property issues, Wood is known as the artist of the unsigned satirical Disneyland Memorial Orgy poster, which first appeared in Paul Krassner's magazine The Realist.[12] The poster depicts a number of copyrighted Disney characters in various unsavory activities (including sex acts and drug use), with huge dollar signs radiating from Cinderella's Castle. Wood himself, as late as 1981, when asked who did that drawing, said only,"I'd rather not say anything about that! It was the most pirated drawing in history! Everyone was printing copies of that. I understand some people got busted for selling it. I always thought Disney stuff was pretty sexy... Snow White, etc."[13] Disney took no legal action against either Krassner or The Realist but did sue a publisher of a "blacklight" version of the poster, who used the image without Krassner's permission. The case was settled out of court.

During the 1960s, Wood did many trading cards and humor products for Topps Chewing Gum, including concept roughs for Topps' famed 1962 Mars Attacks cards prior to the final art by Bob Powell and Norman Saunders. Discovering (from Roy Thomas) that Jack Kirby had returned to DC in 1970, Wood called editor Joe Orlando in an attempt to get the assignment to ink Kirby's new work, but that role was already filled by Vince Colletta.[14] Wood continued to produce periodic work for Marvel during the early 1970s, primarily as inker, and then worked on a handful of comics for DC between 1975 and 1977, producing in particular several covers for Plop!, pencils and inks for issues of All Star Comics in which Wood contributed to the creation of Power Girl by giving her huge breasts and an opening of her costume in the chest which exposes the majority of her breasts, just covering her nipples. Also Wood inked (over Steve Ditko) on Paul Levitz' four-issue miniseries Stalker. Active with the 1970s Academy of Comic Book Arts, Wood also contributed to several editions of the annual ACBA Sketchbook. His last known mainstream credit was inking Wonder Woman #269, cover-dated July, 1980.[15]

Over several decades, numerous artists worked at the Wood Studio. Associates and assistants included Dan Adkins, Richard Bassford, Tony Coleman, Nick Cuti, Leo and Diane Dillon, Larry Hama, Russ Jones, Wayne Howard, Paul Kirchner, Joe Orlando, Bill Pearson, Al Sirois, Ralph Reese, Bhob Stewart, Tatjana Wood and Mike Zeck.

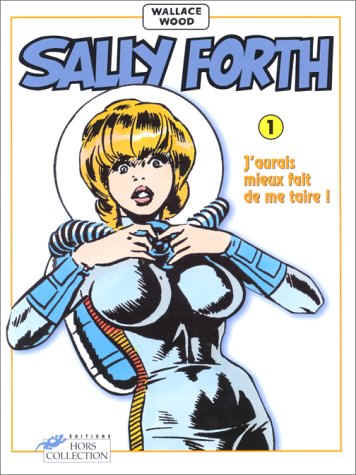

Wood as publisher

In 1966, Wood launched the independent magazine witzend (originally to be titled "et cetera", a name which had to be withdrawn when Wood was told another magazine had already used this) one of the first alternative comics, a decade before Mike Friedrich's Star Reach or Flo Steinberg's Big Apple Comix (for which Wood drew the cover and contributed a story). Wood offered his fellow professionals the opportunity to contribute illustrations and graphic stories that detoured from the usual conventions of the comics industry. After the fourth issue, Wood turned witzend over to Bill Pearson, who continued as editor and publisher through the 1970s and into the 1980s. Wood additionally collected his feature Sally Forth, published in the U.S. servicemen's periodicals Military News and Overseas Weekly from 1968–1974, in a series of four oversize (10"x12") magazines. Pearson, from 1993–95, reformatted the strips into a series of comics published by Eros Comix, an imprint of Fantagraphics Books, which in 1998 collected the entire run into a single 160-page volume.[citation needed]

In 1969, Wood created another seminal independent comic, Heroes, Inc. Presents Cannon, intended for his "Sally Forth" military readership as indicated in the ads and indicia. Artists Steve Ditko and Ralph Reese and writer Ron Whyte are credited with primary writer-artist Wood on three features: "Cannon", "The Misfits",[16] and "Dragonella". A second magazine-format issue was published in 1976 by Wood and CPL Gang Publications. Larry Hama, one of Wood's assistants, said, "I did script about three Sally Forth stories and a few of the Cannon's. I wrote the main Sally Forth story in the first reprint book, which is actually dedicated to me, mostly because I lent Woody the money to publish it".[17]

In 1980 and 1981, Wood did two issues of a completely pornographic comic book, titled Gang Bang. It featured two sexually explicit Sally Forth stories, and sexually explicit versions of Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, titled So White and the Six Dorks; Terry and The Pirates, titled Perry and the Privates; Prince Valiant, titled Prince Violate; Superman and Wonder Woman, titled Stuporman Meets Blunder Woman; Flash Gordon, titled Flasher Gordon; and Tarzan titled Starzan. A third issue, published posthumously, reprinted Wood's 1976-1977 Malice in Wonderland, from National Screw magazine, and other Wood material from Wally Wood's Weird Sex-Fantasy (1977).[citation needed]

"Panels That Always Work"

Wood struggled to be as efficient as possible in his often low-paying work-for-hire.[18] Over time he created a series of layout techniques sketched on pieces of paper which he taped up near his drawing table. These "visual notes," collected on three pages,[19] reminded Wood (and select assistants he showed the pages to)[20] of various layouts and compositional techniques to keep his pages dynamic and interesting.[18] (In the same vein, Wood also taped up another note to himself: "Never draw anything you can copy, never copy anything you can trace, never trace anything you can cut out and paste up.")[19]

In 1980, Wood's original, three-page, 24 panel (not 22) version of "Panels" was published with the proper copyright notice in The Wallace Wood Sketchbook (Crouch/Wood 1980). [21] Around 1981,[19] Wood's ex-assistant Larry Hama, by then an editor at Marvel Comics, pasted up Xeroxes of Wood's copyrighted drawings on a single page, which Hama titled "Wally Wood's 22 Panels That Always Work!!" (It was subtitled, "Or some interesting ways to get some variety into those boring panels where some dumb writer has a bunch of lame characters sitting around and talking for page after page!") Hama left out 2 of the original 24 panels as his Xeroxes were too faint to make out some of the lightest sketches.[21] Hama distributed Wood's "elegantly simple primer to basic storytelling"[22] to artists in the Marvel bullpen, who in turn passed them on to their friends and associates.[20] Eventually, "22 Panels" made the rounds of just about every cartoonist or aspiring comic book artist in the industry and achieved its own iconic status.[22]

Wood's "Panels That Always Work" is copyright Wallace Wood Properties, LLC as listed by the US Copyright Office who assigned the work Registration Number VA0001814764.[23]

Homages and tributes to "22 Panels"

In 2006, writer/artist Joel Johnson bought the Larry Hama paste-up of Xeroxes at auction and made it available for wide distribution on the Internet.[20] In 2010 Anne Lukeman of Kill Vampire Lincoln Productions produced a short film adapting the "22 Panels That Always Work" into a film noir-style experimental piece called 22 Frames That Always Work.[24] Artist Rafael Kayanan created a revised version of "22 Panels" that used actual art from published Wood comics to illustrate each frame.[25] In 2011, cartoonist D.J. Coffman had all 22 panels tattooed onto his left arm.[26] in 2006, cartoonist and publisher Cheese Hasselberger created "Cheese's 22 Panels That Never Work," featuring bizarre situations and generally poor storytelling techniques.[27] In July 2012, http://Cerebus.TV featured Dave Sim's homage to Wally Wood and a focus on his 22 Panels, including a tribute that features a creation using the motif of one of them, depicting Daredevil and Wood himself, in Wally Wood style - and the Wally Wood Estate's official print of the panels.

Personal life and final years

Wood was married three times. His first marriage was to artist Tatjana Wood, who later did extensive work as a comic-book colorist. Their marriage ended in the late 1960s.[3] His second marriage, to Marilyn Silver, also ended in divorce.[3]

For much of his adult life, Wood suffered from chronic, unexplainable headaches. In the 1970s, following bouts with alcoholism, Wood suffered from kidney failure.[3] A stroke in 1978 caused a loss of vision in one eye.[3] Faced with declining health and career prospects, he committed suicide by gunshot in Los Angeles, California three years later.[3] Toward the end of his life, an embittered Wood would say, according to one biography, “If I had it all to do over again, I’d cut off my hands.”[28]

In 1972, EC editor Harvey Kurtzman, who worked closely with Wood during the 1950s, said:

Wally had a tension in him, an intensity that he locked away in an internal steam boiler. I think it ate away his insides, and the work really used him up. I think he delivered some of the finest work that was ever drawn, and I think it's to his credit that he put so much intensity into his work at great sacrifice to himself.[29]

Awards

- National Cartoonists Society Comic Book Division awards, 1957, 1959, and 1965.

- Alley Award, Best Pencil Artist, 1965[30]

- Alley Award, Best Inking Work, 1966[30]

- Best Foreign Cartoonist Award, Angoulême International Comics Festival, 1978

- The Jack Kirby Hall of Fame, 1989[30]

- The Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame, 1992[30]

- The Inkwell Awards Joe Sinnott Hall of Fame Award, 2011.

See also

Audio

- Merry Marvel Marching Society recording includes voice of Wally Wood

- Wallace Wood and Wally Wood at the Grand Comics Database

- Gilbert, Michael T. "Total Control: A Brief Biography of Wally Wood", Alter Ego vol. 3, #8 (Spring 2001). WebCitation archive.

- Wood, Wally. The Marvel Comics Art of Wally Wood. New York: Thumbtack Books, 1982, hardcover. ISBN 0-942480-02-3

External links

- Official Wallace Wood website

- Complete list of Wood's articles for MAD Magazine

- The Wally Wood Letters and photo album. WebCitation archive.

- Stiles, Steve "Wallace Wood: The Tragedy of a Master S.F. Cartoonist", SteveStiles.com, n.d. WebCitation archive.

- "Comic Book Creators Trading Cards #3: Wally Wood" IsThisTomorrow.com, n.d. WebCitation archive.

- Wally Wood (1927 - 1981) American Art Archives. WebCitation archive.

- "Wood", BPIB.com (fan site), n.d. WebCitation archive.

- "Wally Wood". SplashPages.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071205005550/splashpages.com/. Includes "Online checklist: Catalogues, Programs, Sketchbooks, Etc."

Power Girl is a popular character. I would have thought Wally Wood was remembered as much for drawing her as for anything else. To me it seems that the writer of the wikipedia article exaggerates how "huge" her breasts are. I think they're probably comparable to what Lois Lane was originally drawn with. I also think they exaggerate how much skin was showing when Wood drew her with a "Window" in her costume.

But then again, maybe this just goes to show you what Wally Wood was up against. His work never really gained him the respect that it should have, and there were people that didn't like his work, for whatever reason.

The pornographic comics were controversial and my own opinion would be that this kind of stuff doesn't really belong in comics, but most of Wood's output does not belong in that category.

One of many EC comic book covers by Wood.

Wood Art for FIREBALL XL5 lunchbox.

FIREBALL XL5 lunchbox.

Daredevil card.

Wood came up with many interesting concepts, not all of which were used.

Some of Wood's later art, looking a great deal like some of his earlier work.

SALLY FORTH

Wally Wood's "22 Panels That Always Work":

WHAMMO GIANT COMICS was a one-shot, a large size comic book with all kinds of stuff in it. This story was Wally Wood's contribution.

We have seen the enemy and it ain't us.

A

I noticed that the two kids in the Pogo parody are still Goodie Bumpkin and his brunette girlfriend from the strip reprinted just before it.

ReplyDeleteAlso I never did know what L. Sprague deCamp had said against Wally Wood but I DID notice that Wood would run him down every single chance he could, usually with some throwaway line like the one in the Goody Bumpkin strip.

I don't think its a secret that the kid character (here he is Goody) represents Wally Wood, but I do not know whoi the brunette reprsents. The brunette would pop up in his artwork over and over again, usually as a voluptuous adult. I don't think it is meant to represent his wife, his wife looked nothing like that.